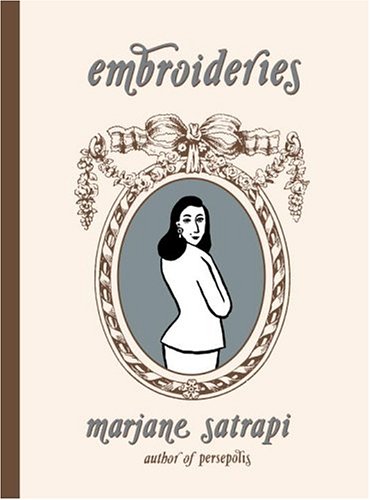

From the Vault: "Embroideries"

I'm on vacation this week, so there won't be much new material posted here over the next few days. As a consolation prize, I thought I'd put up some old reviews I did for The Comics Journal many moons ago. This first one is a review of "Embroideries" by Marjane Satrapi.

“Embroideries” shouldn’t work. At least, not as comics. For one thing, it’s filled with dialogue to the point where the art on several pages offers little more than talking heads. The background art is minimal if existent at all. Often the dialogue is so overwhelming that the book becomes more of an illustrated novel, with the drawings being supplementary to the text instead of collaborating with it on the page.

And yet “Embroideries” does work, almost exceedingly well. A good deal of that is in no small part due to Satrapi’s skills as a storyteller. Her eye for detail, her ear for dialogue and her deliberately simple art style help engage the reader and carry the story along what would otherwise be several rough patches. If nothing else, “Embroideries” proves that Satrapi is no one trick pony.

Which is not to say that Satrapi doesn’t return to familiar themes. “Embroderies,” like the two adjoining volumes of “Persepolis” before it, deals specifically with her and her family, and more generally with life in Iran. Especially, how women survive and thrive in a culture that sees them as second class citizens.

The story takes place several years ago, during the period (one assumes) in “Persepolis 2” where Satrapi had returned to Iran after studying abroad in Europe as a teen-ager. After a large family dinner, the men retire to take a nap while the women gather up large samovars of tea and sit down to gossip.

Once freed of the need to behave as wives and daughters, the women let their hair down and talk honestly about their love lives and sexual experiences. Each one of the women present, it seems, has her own horror story to share, whether it involves an arranged marriage, neglectful boyfriends or just plain lousy lovers.

On the one hand these lurid and at times hard luck stories are an obvious rebuke to the Iranian theocracy and by extension any religious right-wing government or organization that thinks by that merely by imposing their will they can keep people, and especially women, from acting on their sexual impulses. Here are a group of women across the age spectrum, living in one of the most sexually repressive governments in the world. Yet many of them have had premarital sex, had affairs or been someone’s mistresses. And few of them seem the least bit concerned about discussing such topics.

A closer look, however, reveals just how Iran’s chauvinism and its oppressive society have limited these womens’ choices. With few exceptions (most notably Satrapi’s grandmother and aunt) these women define themselves by the relationship to the men in their lives. Though off-stage and much derided, men remain the focal point around which these women revolve. Their fears and anxieties, especially among the younger women in the group, are all based upon their ability to be an ideal Iranian woman, which is to say virginal and pure until marriage, and dutiful and complacent afterward. If these women have made poor choices in love, Satrapi seems to be saying, it is in no small part due to a government and culture that continues to view them as chattel.

The desperation to maintain that illusion of purity is hinted at in the book’s title, which at first glance suggests a benign sewing circle (these days referred to as a coffee klatch), of sorts. It also has more sinister connotations, though, as readers soon learn that “getting an embroidery” is the term in Iran used for a woman having her vagina sutured up again so as to deceive her husband into thinking she’s a virgin on their wedding night.

Certainly, the need to define yourself through your relationship to the love of your life is not a concept alien to Western women (or men for that matter). But the extreme lengths to which these women seem willing to go to in order to hide their indiscretions suggests a fear of repercussion and social shame that is not mirrored here. The women in “Embroideries” live in a phallocentric world and thus are forced to use sly, underhanded means to garner a little bit of power. Satrapi, for example, tells of a friend who resorted to seeing a sorceress in order to get her man to commit. Another woman, for example, describes how she had fat removed from her buttocks used to enlarge her breasts. “Of course this idiot doesn’t know that every time he kisses my breasts it’s actually my ass he’s kissing,” she proudly exclaims.

The book’s slim size is in its favor. If it were any longer, it would start to collapse under the weight of the problems mentioned earlier. Satrapi’s art work is even more minimalist than in “Persepolis” and though charming in the short term, might easily call too much attention to itself in the long. Though successful, in many ways “Embroideries” should be considered a minor work, and not regarded as a true follow-up to the epic sprawl of “Persepolis.” And that’s absolutely fine. After all, there’s nothing wrong with taking a few practice swings before attempting to hit it out of the ballpark once more.

Labels: comics, from the vault

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home